After breast surgery some women are worried about scarring. Besides being visually unappealing some scars may form in problematic fashion causing pain, reducing function, and creating disfiguration [2]. There is not a consensus in the scientific literature to point to a treatment that universally can completely eliminate scarring. Dr. Kim recommends 4 weeks after breast surgery to begin gentle massage in order to care for the scar. But why do scars form to begin with? How is it any different than any other kind of healing?

The act of surgery induces the body’s natural immune response to protect itself. After the surgeon closes the incision a series of events will cause a complex choreography of cells entering and exiting while releasing and responding to chemical messages. The first step of this process is coagulation. Once the platelets have stopped the bleeding in the wound area, the body will go int o a stage of inflammation [4, 7]. The body’s immune response team will remove any possible pathogens and secrete factors that will recruit cells to the area who can grow new tissue to completely seal off the incision in a process called proliferation [4, 7]. Fibroblasts are recruited to the wound; these cells function to create the adhesive and tensile forces necessary to close a wound. Fibroblasts release collagen, glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans; which are critical components to building the support and cushioning needed in the extracellular matrix [4, 7]. These fibroblasts can differentiate into myofibroblasts which release the extracellular matrix contents and also contain a contractile protein, actin, which aids in the process of wound closure [4, 7]. Other cells are recruited to help form the new layer of skin; slowly the cells forming the permanent new layer of skin drive away the factors creating the temporary scar tissue.

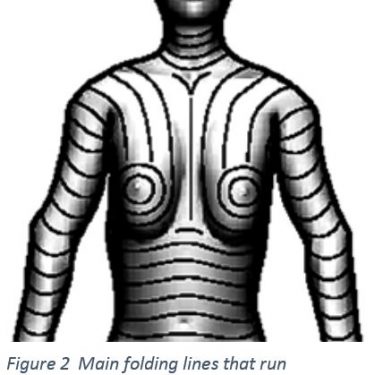

Under normal conditions the fibroblasts will disappear once the wound is closed and new cells have replaced the scar tissue. Sometimes the fibroblasts, will stay at the wound site and continue making connective tissue, creating a thick region of scar tissue as seen in Figure 1 [1]. This thick area of tissue is inconsistent with the skin in the surrounding area creating a difference in topography and a tightened or distorted skin surrounding the scar [3, 7]. The myofibroblasts with their contractile proteins trying to close the wound are not replaced with new skin cells creating a tightened appearance around the healed wound.

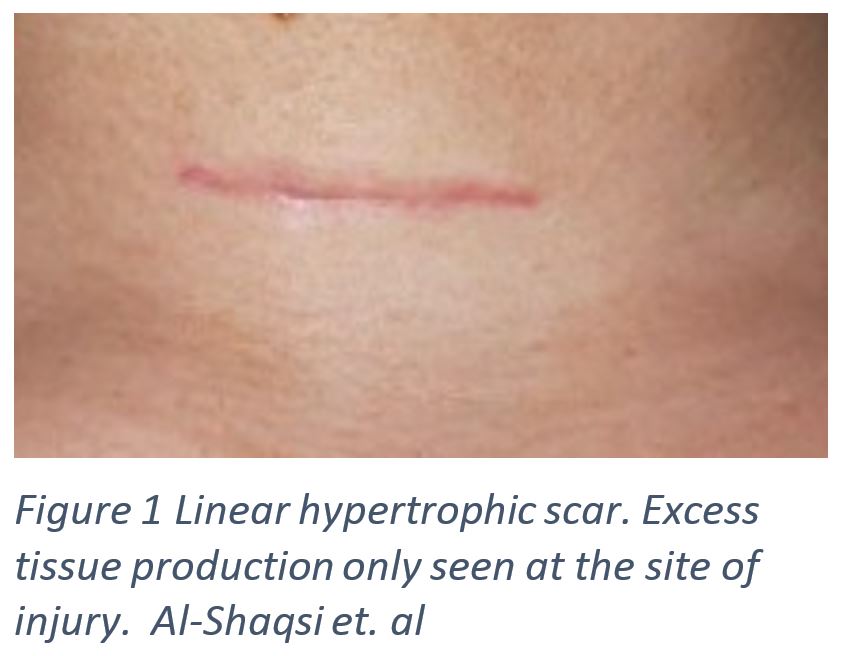

During breast surgery an incision is made and the surgeon closes the procedure using a surgical technique that will minimize tension on the healing incision [5]. This can be achieved by planning incision lines that will lead to the least amount of tension. Dr. Kim will help you to find the incision line that is best to minimize scarring by using evidence based techniques. In Figure 2, suggested incision lines are shown based on the main folding lines, the direction of most laxity determined from studies that have examined hundreds of patients to create a general guideline for surgeons [6]. Although it is still possible that even with excellent incision planning a scar may still form.

To minimize the appearance of a scar there are multiple suggestions Dr. Kim will make including scar massage 4 weeks after surgery. Scar massage has been shown to make the appearance of a scar flatter and more pliable by mechanically distributing any scar tissue away from the concentrated area; it has also been shown to reduce redness [5]. It has also been shows to decrease scar related pain, pruritus (severe itching), and improve patient reported aesthetic outcome [5].

There is still plenty that isn’t known about wound healing, but new research is continually published offering new insights that can contribute to the pursuit of reducing unsightly scar formation and persistence. In February of 2017 an article was published in Science Magazine by Dr. Plikus and colleagues who found that myofibroblasts differentiate into adipocytes, fat cells, and that they may be manipulated in order to treat scars [8]. This preliminary study may change the way scar treatment is approached. Dr. Kim and the members of Northwestern Medical Group are committed to exploring new innovations and evidence based decision making in their practice; during your visit ask about new innovations in the field that may improve your experience.

1. Al-Shaqsi, S., & Al-Bulushi, T. (2016). Cutaneous Scar Prevention and Management: Overview of current therapies. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal, 16(1), e3.

2. Block, L., Gosain, A., & King, T. W. (2015). Emerging therapies for scar prevention. Advances in wound care, 4(10), 607-614.

3. Chen, J., Jia-Han, W., & Hong-Xing, Z. (2005). Inhibitory effects of local pretreated epidermis on wound scarring: A feasible method to minimize surgical scars. Burns, 31(6), 758-764.

4. de la Torre J., Sholar A. (2006). Wound healing: Chronic wounds. Emedicine.com. Accessed 2/23/2017.

5. Khansa, I., Harrison, B., & Janis, J. E. (2016). Evidence-Based Scar Management: How to Improve Results with Technique and Technology. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 138(3S), 165S-178S.

6. Lemperle, G., Tenenhaus, M., Knapp, D., & Lemperle, S. M. (2014). The direction of optimal skin incisions derived from striae distensae. Plastic and reconstructive surgery, 134(6), 1424-1434.

7. Li, B., & Wang, J. H. C. (2011). Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in wound healing: force generation and measurement. Journal of tissue viability, 20(4), 108-120.

8. Plikus, M. V., Guerrero-Juarez, C. F., Ito, M., Li, Y. R., Dedhia, P. H., Zheng, Y., … & Oh, J. W. (2017). Regeneration of fat cells from myofibroblasts during wound healing. Science, aai8792.