According to the “2015 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report” published by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons the total number of body contouring procedures after massive weight loss has increased 12% since last year1; this is almost double the increase in procedures seen from 2013 to 2014, which was only at 7%2. These body contouring procedures include: mastopexy, lower body lift, thigh lift, abdominoplasty, and brachioplasty1,2. Notably abdominoplasty procedures have increased by 26% since 20141.

The increasing prevalence of body contouring procedures is no doubt a result of the increasing numbers of massive weight loss patients who underwent successful bariatric surgery3. Obesity is a major health concern in the United States, with greater than 37% of adult Americans considered obese, and around 8% morbidly obese, according to the Center for Disease Control4. There are a number of comorbidities associated with obesity including: heart disease, stroke, type II diabetes, colorectal cancer, hypertension and others4,5. These obese patients tend to have a propensity for nutritional deficiencies, which can be worsened by bariatric surgery5,6. Massive weight loss can ameliorate many of these risks associated with obesity, although it can also lead to excess skin, which has aesthetic and functional consequences as well as further nutritional concerns5,6.

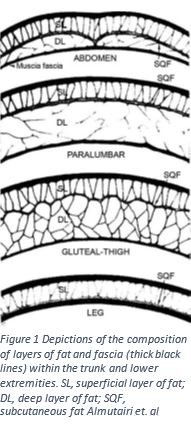

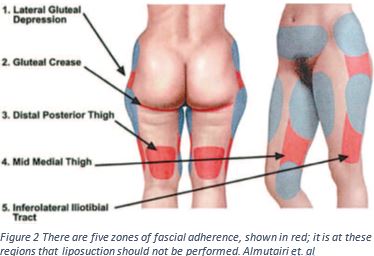

These body contouring procedures often require removal of skin through large incisions, liposuction, and may be performed instages3,5. Although in order to fully understand the procedure it is first key to understand the anatomy of the region. Between the skin and the muscle below there is an entire system of fascia and fat3,7. Fascia is thin fibrous tissue that encloses muscle; it acts as an enclosing, anchoring and stabilizing structure3. Figure one shows the different components of the contents between fascial layers. There are two compartments of subcutaneous fat, the superficial and deep layer3. The superficial layer of fat is dense and tightly packed with nerves and vessels; any disturbance of this layer must be done with care to prevent risk of complications3. The deep layer is where liposuction is normally performed3,7. The superficial fascia will meet the deeper layer of fascia in areas known as the zones of adherence3,7. These are the points that create a barrier between and within layers similar to bubble wrap. If these zones of adherence are interrupted by liposuction it could lead to contour defects3,7. By understanding the nature of layers and compartments beneath the skin, the surgeon can reshape the form of the body.

The massive weight loss patient may have an increased risk of postoperative complications including wound healing problems, wound infections, hematomas, seromas, and venous thromboembolism8. There is also a risk of nutritional deficiency. It has been shown that after bariatric surgery patients tend to have a decrease in their consumption of protein, which can further exacerbate poor wound healing6. It is critical to wait 12-18 months after bariatric surgery before body contouring procedures6,8. Patients who are to undergo a body contouring procedure should be carefully screened to ensure safety and take an active role in promoting their health.

Body contouring following bariatric surgery can improve a patient’s body image and overall wellness. In a 2015 study, Tremp and colleagues found that body contouring procedures produce long lasting and high patient satisfaction9. Poulsen and colleagues found that patients believe their surgery improves their appearance, ability to be physically active, ameliorates self-confidence issues, and generally improves their quality of life10. If you are considering undergoing bariatric surgery or have recently lost a massive amount of weight consider speaking to a plastic surgeon about body contouring to determine if this type of surgery is right for you.

1. American Society of Plastic Surgery. (2015). 2015 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report: ASPS National Clearinghouse of Plastic Surgery Procedural Statistics. Arlington Heights, IL.

2.American Society of Plastic Surgery. (2014). 2014 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report: ASPS National Clearinghouse of Plastic Surgery Procedural Statistics. Arlington Heights, IL.

3. Almutairi, K., Gusenoff, J. A., & Rubin, J. P. (2016). Body Contouring. Plastic and reconstructive surgery, 137(3), 586e-602e.

4. “Adult Obesity Facts.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 01 Sept. 2016. Web. 07 Dec. 2016.

5. Katzel, E. B., Shakir, S., Kostereva, N., Lannau, B., Gimbel, M., Nguyen, V. T., … & Gusenoff, J. A. (2016). Abnormal Vessel Architecture Persists in the Microvasculature of the Massive Weight Loss Patient. Plastic and reconstructive surgery, 137(1), 24e-30e.

6. Xanthakos, S. A. (2009). Nutritional deficiencies in obesity and after bariatric surgery. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 56(5), 1105-1121.

7. Rohrich, R. J., Smith, P. D., Marcantonio, D. R., & Kenkel, J. M. (2001). The zones of adherence: role in minimizing and preventing contour deformities in liposuction. Plastic and reconstructive surgery, 107(6), 1562-1569.

8. Shermak, M. A. (2012). Pearls and perils of caring for the postbariatric body contouring patient. Plastic and reconstructive surgery, 130(4), 585e-596e.

9. Tremp, M., Delko, T., Kraljević, M., Zingg, U., Rieger, U. M., Haug, M., & Kalbermatten, D. F. (2015). Outcome in body-contouring surgery after massive weight loss: a prospective matched single-blind study. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery, 68(10), 1410-1416.

10. Poulsen, L., Klassen, A., Jhanwar, S., Pusic, A., Roessler, K. K., Rose, M., & Sørensen, J. A. (2016). Patient Expectations of Bariatric and Body Contouring Surgery. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Global Open, 4(4).