In a 2016 journal article authored by members of Dr. John Kim’s research team, published in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, the issue of seroma in prosthetic breast reconstruction was evaluated. A seroma is a serous fluid pool that can form after surgery on the breast (2). Seroma is such a common postoperative complication that it is considered a side effect of surgery versus termed a complication (2, 7). The incidence of seroma after breast surgery rages from 0.2 to 20% (3, 1). Seromas can cause patient distress, increased cost due to increased office visits, unacceptable aesthetic outcomes, and infection (1). In order to improve patient experience and reduce the incidence of seroma formation, Dr. Kim’s research team investigated the current literature to determine what guidelines and strategies could help to reduce and treat seromas.

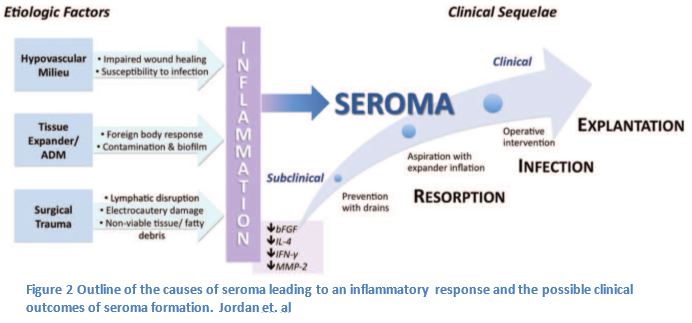

In order to make suggestions on how to reduce the incidence of seroma it was important to identify the factors that contribute to seroma formation. The following variables associated with the process of breast reconstruction surgery may contribute to the formation of a seroma: mastectomy, insertion of an implant, lymph node dissection, and the confluence of side effects from undergoing surgery (1,2,4). It is still unclear whether the composition of seroma is lymph or inflammatory exudate, fluid filtered from the circulatory system. (6,1,5).

It has been long established that drains can counteract the effect of the dead space created after mastectomy and axillary dissection on seroma formation. Drains have been used to accelerate wound healing, reduce risk of infection, and necrosis (2, 8). Patients can also be discharged with drains to further reduce risks of complications (2 9).

The drains can manage the build up of lymph in the breast capsule and axilla, but other aspects of the surgical process may lead to an immune response, which may lead to a seroma. The insertion of an implant, foreign body, can incite an immune reaction which may lead to the build up of fluid causing the seroma; furthermore a small bacterial contamination could lead to prolonged inflammation (1). To reverse this risk implants are treated with an antibacterial solution before placement in the breast capsule (9).

Finally there are a number of factors due to surgical trauma, which may increase the serous fluid collection within the breast capsule (1, 4). Some of the surgical tools used during surgery may be related to the development of seroma (4). This is seen in the inherent damage that can be caused by a disruption of the lymphatics, electrocautery associated tissue damage, and the possible production of fatty debris or nonviable tissues that could increase the inflammatory fluids (1,4).

In order to better manage seroma, there are measures that the surgeon will take to prevent any additional secondary complications (1). Any patient with a detectable seroma is treated with antibiotics to reduce the risk of infection (1). A larger seroma may be treated with aspiration and expansion of the prosthetic implant to reduce any dead space (1, 10). Only after these attempts will a persistent seroma be treated with reoperation to drain the seroma (1, 11).

While is difficult to eliminate all risks associated with surgery, the risk of seroma in breast reconstruction can be reduced. There are multiple attempts by the surgeon to prevent, identify, and treat seromas before they may indicate secondary complications. This article by Dr. Kim’s research associates lay out the issues associated with seroma and methods used to reduce their incidence. There is certainly further study needed, but with this contribution to the literature future studies may find new innovative ways to improve patient experience.

1. Jordan, S. W., Khavanin, N., & Kim, J. Y. (2016). Seroma in Prosthetic Breast Reconstruction. Plastic and reconstructive surgery, 137(4), 1104-1116.

2. Srivastava, V., Basu, S., & Shukla, V. K. (2012). Seroma formation after breast cancer surgery: what we have learned in the last two decades. Journal of breast cancer, 15(4), 373-380.

3. Cordeiro PG, McCarthy CM. A single surgeon’s 12-year experience with tissue expander/implant breast reconstruc- tion: Part II. An analysis of long-term complications, aes- thetic outcomes, and patient satisfaction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:832–839.

4. Yilmaz KB, Dogan L, Nalbant H, et al. Comparing scalpel, electrocautery and ultrasonic dissector effects: The impact on wound complications and pro-in ammatory cytokine lev- els in wound uid from mastectomy patients. J Breast Cancer 2011;14:58–63.

5. Montalto E, Mangraviti S, Costa G, et al. Seroma uid sub- sequent to axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer derives from an accumulation of afferent lymph. Immunol Lett. 2010;131:67–72.

6. Loo WT, Sasano H, Chow LW. Pro-in ammatory cytokine, matrix metalloproteinases and TIMP-1 are involved in wound healing after mastectomy in invasive breast cancer patients. Biomed Pharmacother. 2007;61:548–552.

7. Kumar S, Lal B, Misra MC. Post-mastectomy seroma: a new look into the aetiology of an old problem. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1995;40:292–294.

8. Moss JP. Historical and current perspectives on surgical drainage. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1981;152:517–527.

9. Ooi, A. S., & Song, D. H. (2016). Reducing infection risk in implant-based breast-reconstruction surgery: challenges and solutions. Breast Cancer: Targets and Therapy, 8, 161.

10. Park JE, Nigam M, Shenaq DS, Song DH. A simple, safe technique for thorough seroma evacuation in the outpa- tient setting. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2014;2:e212.

11. Spear SL, Seruya M. Management of the infected or exposed breast prosthesis: A single surgeon’s 15-year experience with 69 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010; 125:1074–1084.

12. Dhillon, G. S., Bell, N., Ginat, D. T., Levit, A., Destounis, S., & O’Connell, A. (2011). Breast MR imaging: what the radiologist needs to know. Journal of clinical imaging science, 1.